|

Early Scandinavian Sources to Harps and Harp Playing by Lia Lonnert There is no period in Scandinavian history that has such a magical sound to its name as the Viking era (ca 800-1050 AD). Its myths, runes, gods and Vikings going berserk on raids are all part of the mythology and magic. Harps and harp playing have a part in these myths and may be a part of the reality during this era. Texts, pictures and archaeological finds of stringed instruments tell us fragments of the music-making of the early Scandinavians. Some of the sources presented in this article are as late as the 13th century, but have or may have a connection with mythology and legends of past periods. 6th Century Lyre The oldest preserved image of a stringed instrument from a Nordic country is on a stone from Gotland, an island situated east of Sweden. It was carved in the 6th century and probably represents a lyre. The context of the lyre on this stone is unknown: it might portray a real instrument, it might be an illustration for a myth or story, or maybe it had a magical purpose. (Picture 1).

Picture 1, A picture of a lyre. Lärbro, Källstäde, Gotland, Sweden 6th century Icelandic Myths About 1150 A.D. scholars in Iceland began recording pre-Christian myths and religion. Iceland had been officially Christian since the year 1000 (or 999) but pagan rites continued to be practiced parallel with Christian rites. The scholars who collected the myths were Christian, but the reasons to collect the myths were not just to preserve them, as we would today, but also were political, to show that Iceland had a mythological history as old and interesting as Greece’s or Rome’s, and to create an Icelandic identity separate from Norway, the country from which Iceland was colonized. However, it must be noted that when this oral tradition was recorded it had already been influenced by Christianity; therefore the Icelandic sagas and myths are an unreliable source to pre-Christian mythology. Poetic Edda; Voluspa In the first part of the book called the Poetic Edda, the oldest preserved writing is from the end of the 13th century. In it myths from oral tradition are collected, some of which may have origins from the 9th century or even earlier. The very first song, Voluspa, the prophecy of the seeress, describes the creation of the world and how it will end in ragnarök, (in English called the twilight of the gods or maybe better known as the German Götterdämmerung). In this song one verse tells us about Eggder, the shepherd of the giantess. “Sitting on the mound striking his harp was the gladsome Eggder, the giantess’ shepherd. Above him in a tree a beautiful red cockerel crowed, whose name was Fjalar”. This is all symbolic, as Eggder is no ordinary shepherd; the mound is a burial mound; he is not guarding sheep but wolves who will fight at the final battle at ragnarök; and the cockerel that crows in the gallow tree is one of the signs of the approaching ragnarök. Gunnar in the Snake Pit The second part of the Poetic Edda tells the story of Sigurd the dragon slayer, a legend that exists in different versions and sources in areas that speak Germanic languages. Besides several Icelandic versions, one of the main texts is the Germanic Nibelungenlied. The harp appears in some of the Icelandic versions of the legend, and in the Germanic Nibelungenlied the fiddle has the role of a magic instrument. Another difference is that the Nibelungenlied is set at a Christian court while the Icelandic versions has a pagan setting. The harp is mentioned in four different versions, by different authors, of the execution of the hero Gunnar in the Poetic Edda. Three are poems and one tells the story in prose. A condensed version of the main event: Gunnar is punished by Atli, better known as Attila the Hun, by being thrown in a snake pit. Gunnar plays his harp in the pit but is bitten by a snake and dies. 1. In the probably oldest version, Atlakviða, that might originate from the 10th century, Gunnar strikes the harp angrily in the snake pit. 2. In Atlamál in grænlenzku Gunnar plays the harp with his toes since his hands are tied. Women cry and men moan and complain when they hear his playing. 3. In Oddrúnarkviða, we are told the story a bit differently. Oddrun, who is Atli’s sister, loves Gunnar. She is visiting another court to help with a delivery of a child. She hears at a distance Gunnar playing his harp and understands that he is asking for her help. She arrives too late to save him. In Oddrun’s lament, the snake that kills Gunnar is Atli’s mother in disguise. 4. The version in prose is probably the latest version in the Poetic Edda. Maybe it was written when the collection of songs was put together. In this version, the snakes are lulled to sleep by Gunnar’s harp playing. Possibly this part was written by Snorri Sturlasson in the beginning of the 13th century. 5. Snorri has a similar version in his book called Snorris Edda. In the last version of this story of the Völsunga saga, probably from the 14th century, the harp is thrown into the pit by Gudrun, Gunnar’s sister and Atli’s wife. It also tells that Gunnar played the harp more beautifully with his toes than others play with their fingers. (Picture 2).

Picture 2. Gunnar playing a harp with his toes. Uvdal kirke, Numedal, Norway. 13th or early 14th century Iconography of Gunnar There are eight pictures of Gunnar playing harp in the snake pit in areas that now are Norway and Sweden. The oldest of these is on the outer side of a baptismal font and originates from the 12th century, the instrument shown is what we today would call a lyre. Several of these pictures are from the doorframes to churches and are dated to the 13th century. Some of them show Gunnar playing a lyre-like instrument and some a harp. The word “harp” probably could be used for different stringed instruments, and the lyre was probably more common than the harp in the Nordic countries. There are different theories why this pre-Christian motif is presented on churches and fonts. One is that it represents the pagan world outside the church or the font; another that the legend could be used theologically to explain Christian beliefs with local myths. It is also possible that the motif had no theological connections at all: maybe the reasons were political, to strengthen the power of a king who was considered related to these mythical heroes in the legends, or perhaps they were just contemporary fashionable artistic expressions. (Picture 3).

Picture 3. Gunnar playing a harp with his toes. Näs kyrka, Jämtland, Sweden. 13th or 14th century. Orfeus and David Parallels with other players of stringed instruments, such as Orfeus and David, are difficult; this definitely sounds more…pagan. The Voluspa has been dated to the 11th century, but might be older. It is not known how old the verse containing Eggder is. A stone carving on the Isle of Man, situated between Ireland and Great Britain, shows a man playing the harp. It is dated to the 11th century and probably portrays King David. Isle of Man was Danish territory during that time and the stone pictures have Scandinavian influences and Scandinavian pagan designs. Other influences are also possible, as contemporary and older Pictish and Irish stones show harps and other stringed instruments. (Picture 4).

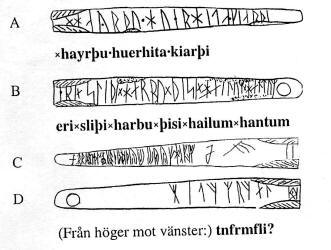

Picture 4, a lyre from a picture stone called Mal Lumkun cross or Kirk Michael 104. Isle of Man, 11th century. Aslaug, Daughter of Sigurd the Dragonslayer One of the sources of the legend about Sigurd, the Völsunga saga, contains the sequel Ragnar Lodbroks saga. In this the story is told about Aslaug, daughter of Brunhild the Valkyre and Sigurd the dragonslayer. To prevent Aslaug’s being killed by enemies, the old king, Heimer, flees with her to Norway. He keeps her hidden inside a harp, and when there is no longer danger he lets her out. When she cries he plays the harp for her. This is the earliest part of an Icelandic saga in which an instrument we would call a harp is described, and it has to be big enough to hide a three-year- old child. More Scandinavian Sagas Several other Icelandic sagas tell us about harp playing. Some contain a lot of magic like the amazing Bósa och Herrauðs saga, others just give everyday information that, for example, a harpist played at a party. A saga from the 14th century, Bárðar saga snæfellsáss, describes the first female harpist, Helga. She plays the harp at night when she cannot sleep. There are several other texts with possible connections to Nordic harp playing like the old-English Beowulf and the description of a burial written by the Arabic traveler Ibn Fadlan. The problem with written and iconographical sources is that it is difficult to know if they have any connection with actual real instruments or music-making at the time. They can have other purposes, for example magical, political, traditional, etc. Archeological Finds Comparisons with other sources, especially archaeological finds, are possible. Some instruments or fragments of instruments have been found in graves. Other discoveries are items that were lost, broken or not finished. A comparison between remains of harps and lyres shows that lyres have more parts that easily can be preserved and identified like bridges and string holders. Most parts of harps are made of wood. The parts that are possibly made of metal or bone such as rivets or tuning pins are difficult to identify solely as harp parts. There are a few archaeological finds from Scandinavia and areas connected to Scandinavia. All of these probably are fragments of lyres. Also a lyre from the 14th century is preserved in Norway, the Kravik lyre. An interesting find from Sigtuna, in Sweden, was made a few years ago: a tuning key decorated with runes. The text reads “Erri made this harp with wholesome hands”. This is the earliest find of a medieval tuning key and may originate from the 12th century, and is also the oldest Scandinavian source to the word “harp”. (Picture 5).

Picture 5. Tuning key decorated with runes. Sigtuna, Sweden12th century. It appears that the word “harp” could be used for different plucked instruments during the Viking and medieval era in the Nordic countries. The lyre seems to be the oldest instrument. The first source to identify a triangular harp is a manuscript from the 14th century but probably it is a copy of an older manuscript. Pictures and texts often present harps and harp playing in a magical context. It is possible that the instruments in the sources are mostly mythological and have very little to do with contemporary instruments. Archaeological finds present traces of stringed instruments being played, but the finds are so few that it is hard to build theories of who played the harp, when they played and what the instrument looked like. If you read Swedish you might want to see Harpan i ormgropen – om källor till vikingatida stränginstrument ["The Harp in the Snakepit - on the Sources of Viking Stringed Instruments"] by Lia Lonnert, 2006. To obtain it, please write to Lia at lialonnert@spray.se There are several

translations of Icelandic sagas available on the net. Sources for illustrations.

Picture 1.

Picture 2. Picture 3.

Picture 4.

Picture 5. |

| [To author biography] | [Back to top of page] |

Historical Harp | Folk and World Harp | Pedal Harp |

Harp Building | Harp Works | Non-Harps |

Camps & Concerts | Links | Glossary |

Donate! | Get Involved! | Contact Us | About Harp Spectrum

Copyright 2002 - 2017, Harp Spectrum All Rights Reserved